Life & Legacy

Brian Friel (1929-2015) is widely regarded as one of Ireland’s greatest playwrights and a hugely accomplished short story writer. His plays, including Dancing at Lughnasa, Philadelphia, Here I Come!, Translations, and Faith Healer, continue to captivate audiences worldwide. Often hailed as "Ireland’s Chekhov," Friel’s plays explore themes of identity, language, memory, and the human condition, drawing deeply on the cultural and political landscape of the north west of Ireland, in particular Derry and Donegal. In 1980 in Derry, he established Field Day Theatre Company with actor Stephen Rea. The company toured plays throughout Ireland and became a hugely important cultural force during the dark years of the ‘Troubles’. His legacy lives on through the timeless relevance of his works. Friel plays continue to entrance audiences across the globe.

Brian Friel was born in Knockmoyle, near Omagh, County Tyrone on January 9, 1929. The family moved to Derry when Brian was ten years old. He was educated at St Columb’s College, Derry before attending St Patrick's College, Maynooth and then training as a teacher at St Joseph's Training College, Belfast. Brian taught in Derry from 1950 until 1960 until a contract from the New Yorker magazine enabled him to leave teaching and pursue a career as a writer. In the late 1960s, the Friel family moved from Derry to Muff, County Donegal before settling finally in nearby Greencastle. He passed away on October 2, 2015, and was laid to rest in the graveyard in his beloved Glenties.

Glenties in Donegal

Glenties was home to Friel’s mother’s people and the young Friel spent childhood summers there.

“Glenties, above all, had a special hold on his heart and on his imagination. Those childhood summers in the Laurels Cottage, in the company of his mother’s family, were formative in so many ways. The accumulated memories helped shape the writer he would become, whether in the short stories or the plays. The cottage, the lakes he fished with his father, the landscape and the people hovered over the writing desk throughout his life. If Brian was part of Donegal, Donegal was very much a part of him.”

Friel’s grandfather was the stationmaster in Glenties, and the house was originally the station house. When Brian got off the train at the rail terminus in Glenties, it was just a step across the road to ‘The Laurels’. In Self-Portrait (1971), Brian Friel recalled:

“When I was a boy we always spent a portion of our summer holidays in my mother’s old home near the village of Glenties in County Donegal. I have memories of those holidays that are as pellucid, as intense, as if they happened last week. I remember in detail the shape of the cups hanging in the scullery, the pattern of flags on the kitchen floor, every knot of wood on the wooden stairway, every door handle, every smell, the shape and texture of every tree around the place”

His play Dancing at Lughnasa (1990) is dedicated to “those five brave Glenties women” referring to his mother Christina McLoone and his four aunts who grew up in ‘The Laurels’ and are now immortalised as the Mundy sisters of the play. His uncle, Barney McLoone served as inspiration for the missionary priest who returns home in the play. The last McLoone sister, Maggie, lived in ‘The Laurels’ until her death in the late 1950s when the house was bought by a local family. Such is the significance of the ‘The Laurels’ to the play that when the 1998 film version was released, Brian Friel along with actresses Meryl Streep and Sophie Thompson unveiled a plaque on the house on September 24, 1998.

Ballybeg

Almost every Brian Friel play is set in Ballybeg, Co Donegal, his village of the mind. When the playwright was laid to rest in Glenties, Co Donegal in October 2015, the village was renamed Ballybeg for the day. The landscape, the atmosphere, the very spirit of the place informs and inhabits his work. If Ballybeg is anywhere, it is Glenties.

Inspiration and setting

In creating Ballybeg, Brian Friel immortalised not just a fictional town, but the spirit of Glenties—a place that, through his eyes, became a universal symbol for the human experience. Through Friel’s plays, Glenties lives on as the emotional heart of Ballybeg. Whether on stage or in Donegal, the legacy of Glenties as the inspiration for Friel’s world is undeniable, offering a rich cultural and emotional landscape that continues to inspire and captivate audiences around the world.

Ballybeg (or Baile Beag) – the fictional County Donegal town in which Friel set his works such as Philadelphia, Here I Come! (1964), Translations (1980), Dancing at Lughnasa (1990), and The Home Place (2005) – has become synonymous with, and is clearly based on, Glenties.

In the MacGill Summer School brochure (1981), Friel wrote that:

“A community that celebrates a local writer does two things. Rightly and with pardonable pride, it participates in the national/international acclaim. And rightly, and indeed as importantly, it celebrates itself because the writer is both fashioned by and fashions his people. Because of my own close connections with Glenties – it occupies a large portion of my affections and permanently shaped my imagination. ”

Plays

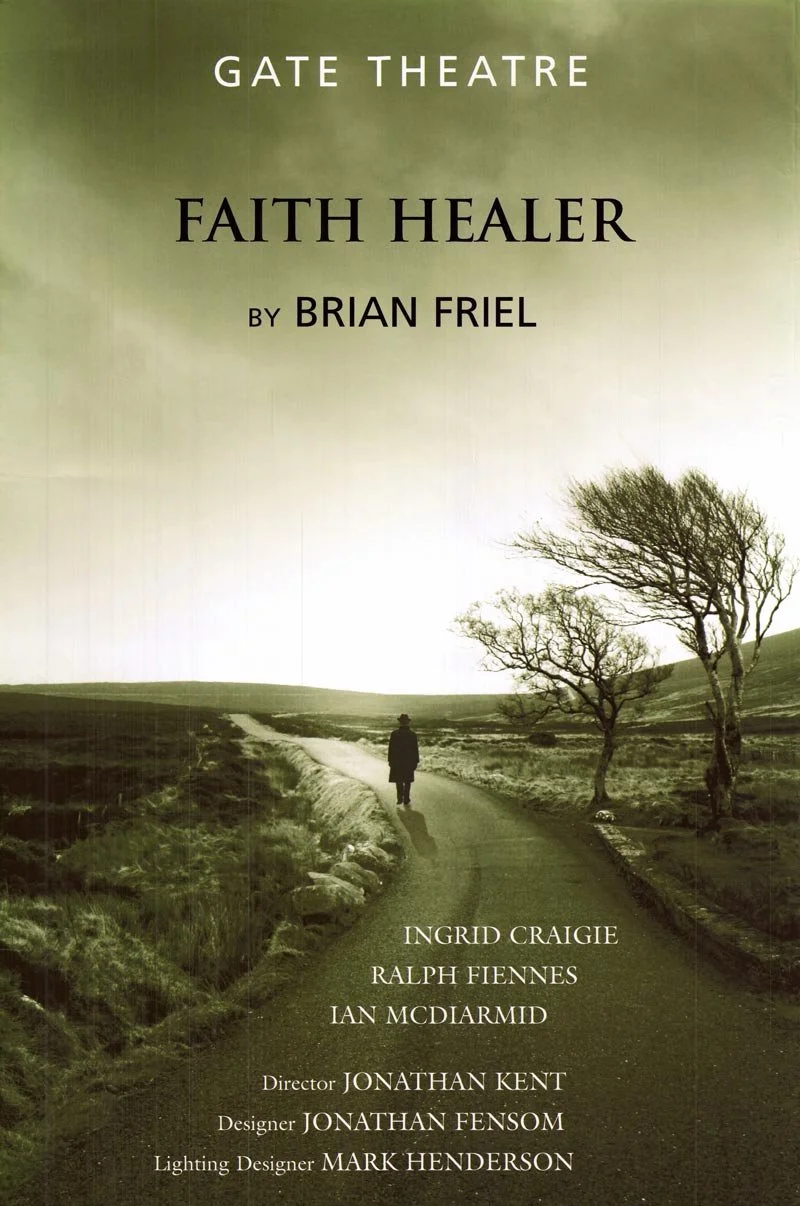

“A wondrous ... work fit to be placed alongside the greatest in Irish drama”

“Friel’s plays are eloquently lyrical rather than packed with action, and Faith Healer is no exception — we’re told about events, not shown them”

Translations (1980)

Set in Ballybeg, County Donegal in 1833, Translations is one of Friel's most acclaimed plays. It explores the effects of British colonization on the Irish language and culture through the lens of a small rural Irish village. British soldiers map out the Irish landscape, erasing Gaelic place names and replacing them with English ones.

Dancing at Lughnasa (1990)

Perhaps Friel’s most famous play, Dancing at Lughnasa is a semi-autobiographical story set in 1936. It focuses on the lives of five unmarried sisters living near the fictional village of Ballybeg. It draws on Friel’s memory of his aunts’ life in The Laurels, Glenties, County Donegal . Narrated by their nephew, Michael, the play revisits an eventful summer. The play's portrayal of memory, family, and the struggle to maintain dignity in the face of hardship earned it widespread acclaim, including a Tony Award for Best Play in 1992.

Philadelphia, Here I Come! (1964)

This early work marked Friel’s arrival as a major playwright. It tells the story of Gar O'Donnell, a young Irishman on the eve of his emigration to America. The play uniquely presents Gar in two forms: "Public Gar," who interacts with the world, and "Private Gar," who expresses his inner thoughts and emotions. The play took the Dublin Theatre Festival of 1964 by storm before transferring to Broadway and an American breakthrough.

Faith Healer (1979)

Faith Healer is a powerful meditation on memory, belief, and truth. It tells the story of Frank Hardy, an itinerant faith healer, and his troubled relationships with his wife Grace and his manager Teddy. The play is structured in four monologues, with each character recounting their version of events, creating a compelling exploration of the elusive nature of reality and the human need for stories and meaning. It is widely regarded as Friel’s masterpiece.

The Freedom of the City (1973)

This political drama, set during the Troubles in Northern Ireland and drawing significantly on the events of Bloody Sunday in Derry in January 1972, focuses on three civil rights protesters who take refuge in the Guildhall after a protest march in the city. Friel explores the nature of truth, the human cost of political violence and the socio-political tensions in Northern Ireland. It is perhaps Friel’s most overtly political play.

Short Stories

“stories I rate with some of the best short stories ever written, and Mr Friel has created a world as real and poignant as Chekhov or Camus stories”

“Each of these stories is set in the northwest of Ireland and deals with the everyday faiths and hopes which help their characters to survive. In many of them there is make believe and illusion, the necessary self-deceptions which enhance memory. In all of them there is humour, resilience and dignity. They are told with the sureness and tact of a master. ”

In addition to his celebrated plays, Friel was a skilled short story writer. Read the stories carefully and you will find many of the themes and preoccupations that recur throughout the plays. It is as if the stories lay the groundwork for the drama to come.

The Saucer of Larks (1959)

“He was a young airman from Hamburg and he crashed into that stump of a hill over there. It was a night in the summer of ’42 and his plane was burned to ashes… The fishermen found him about fifty yards from the plane. They made a grave and laid him to rest”

Two Germans, employed by the German War Graves Commission, were in the Irish countryside to find the grave of a German airman, killed there in 1942. They plan to take the remains to a special cemetery in County Wicklow, where there are already over fifty Germans buried. Inspired by Maghergallen in County Donegal.

Foundry House (1961)

“The ground rose rapidly in a tangle of shrubs and wild rhododendron and decaying trees, through which the avenue crawled up to the Foundry House at the top of the hill”

Joe and his family move back to the gate house of a large estate where he grew up. The family in the ‘big house’ invite him to do some work. Joe is in the house when they play a tape recording from one of the daughters, a missionary nun in Africa, a scene that later finds its way into the play Aristocrats.

The Diviner (1962)

“The diviner was a tall man, inclined to flesh, and dressed in the same deep black as Nelly and the priest. He wore a black, greasy homburg, tilted the least fraction to the side, and carried a flat package, wrapped in newspaper, under his arm. The first impression was, What a fine man! But when he stepped directly in front of the headlights of one car there were signs of wear – faded, too active eyes, fingernails stained with nicotine, the trousers not a match for the jacket, the shoes cracking across the toecap, cheeks lined by the ready smile. He spoke with the attractive lilting accent of the west coast”

The Diviner, centres on Nellie Doherty, a widow whose husband has died unexpectedly. After a brief courtship, Nellie remarries and just when it seems that she has found happiness and dignity again, her second husband is drowned in a boating accident. The Diviner is a story of a man who possesses a seemingly magical ability.